Semaphore is open source. Check out our GitHub repo and consider giving us star ✨

Automated testing feels like a given. But it wasn’t always this way. Testing had humble roots in resource-limited mainframes in the 50s. Its history is often overlooked, but it is a good proxy for the evolution of software development.

Early Days

Before sprints and DevOps, software testing was a manual affair. Computer power was scarce and memory reserved for important things (which didn’t include testing).

Software development was conducted on large centralized systems shared by multiple teams. With time slotting, researchers had to book time on the mainframe in advance, and every second of compute time had to count. Testing was a luxury.

Some automation did exist, but it was mostly confined to large enterprises with the resources to build bespoke testing tools. The concept of unit testing was known in academic circles and some large-scale systems, but there was no standardized or widely adopted approach. Instead, most testing was ad hoc.

Misunderstood Waterfall

In 1970, Winston W. Royce, software engineer, published a paper titled Managing the Development of Large Software Systems. This paper would become the foundation of what we now call the Waterfall model, and maybe one of the most misunderstood documents in software history.

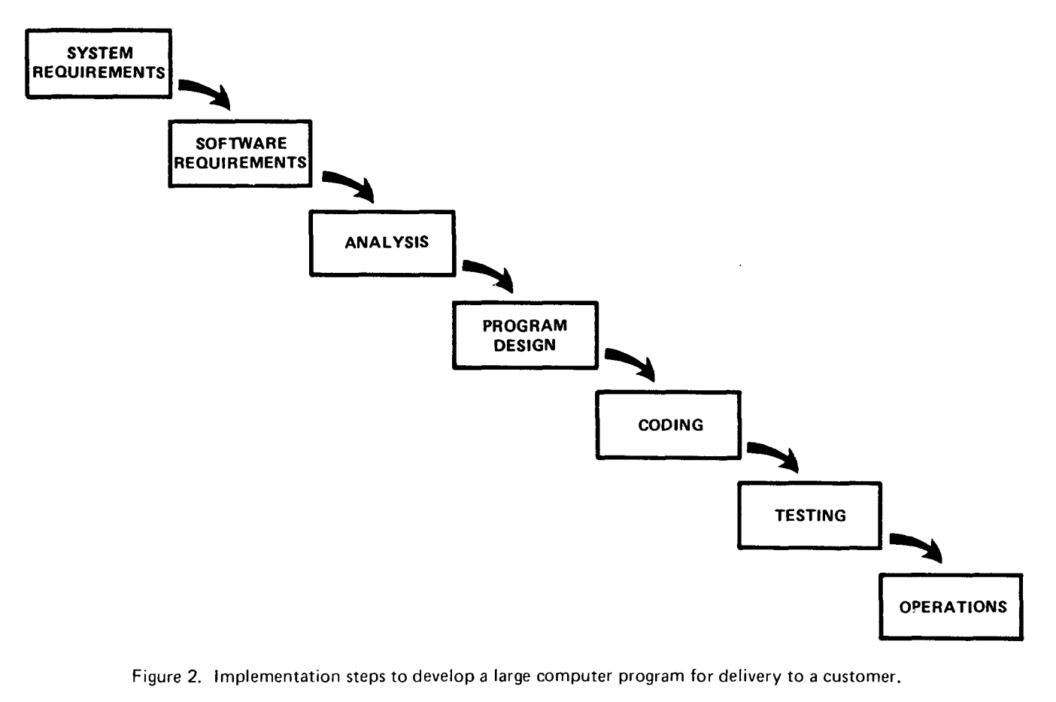

Royce outlined the steps that were common currency on software development at the time. It all made sense to design-driven, engineering professionals from that era: begin with analysis, then proceed to design, implementation, testing, and finally deployment. Each step was arranged linearly, cascading downward like a waterfall.

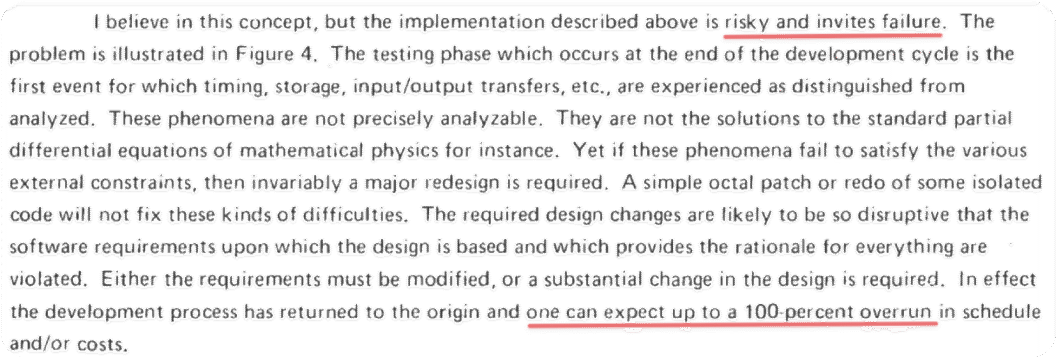

But Royce never advocated for this rigid, linear approach. In fact, he was deeply critical of it. Just one page after presenting the now-famous diagram, Royce warned that the model was risky and almost guaranteed to fail. He emphasized that deferring testing until the end of the development cycle meant discovering design flaws far too late, resulting in costly rework and missed deadlines.

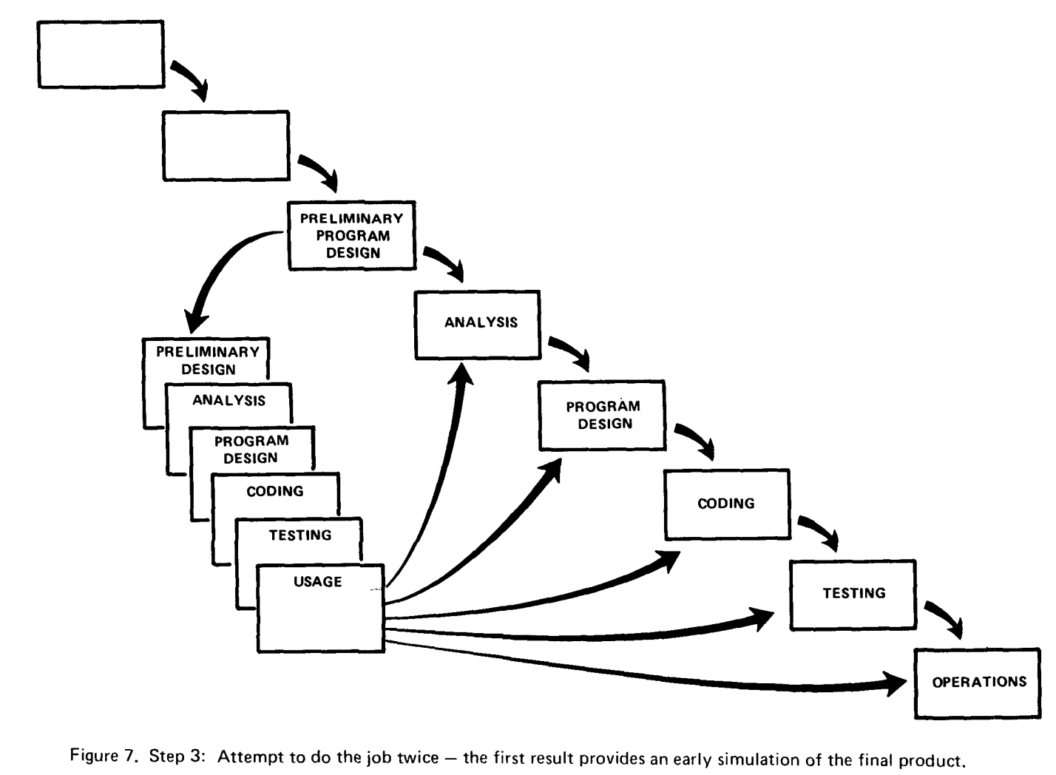

Royce went further, suggesting more iterative approaches to development. He recommended doing the process twice: once on a smaller scale as a prototype, and then again for the actual product. Ironically, few people actually read Royce’s full paper. Most just saw the diagram on page two, ignored the warnings, and adopted the linear model as best practice. For decades, software teams followed this blueprint, believing it to be proven and effective. When in reality, it was a cautionary tale.

Manifesting Agile

By the 1990s, the cracks in the Waterfall model were undeniable. Projects were consistently over budget, behind schedule, and misaligned with user needs. Royce had always been right: a rigid, plan-driven approach that delayed feedback and testing until it was too late to change course.

In 2001, seventeen software practitioners came together at a ski resort in Snowbird, Utah, and drafted the Agile Manifesto. It was a simple document with a powerful message: software development should prioritize people and working code over rigid processes.

The manifesto laid out four core values:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

Agile and Extreme Programming (XP) promoted iterative development, continuous feedback, and frequent releases. Testing was no longer an isolated phase. It became an integral part of the development loop, happening alongside coding.

Agile brought testing out of the shadows. Testing became a shared responsibility, not just something handed off to QA at the end. Practices like Test-Driven Development (TDD) and Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) emerged directly from this mindset shift, encouraging developers to write tests before writing code and to focus on behavior over implementation.

SUnit and Testing Frameworks

The shift to Agile transformed how it was tested. As teams embraced shorter iterations and continuous feedback, there was a growing need for tools that could keep pace with rapid development cycles. This need gave birth to the xUnit family of testing frameworks.

It all started with SUnit, “The Mother of All Testing Frameworks”, created in 1989 by Kent Beck for the Smalltalk programming language. SUnit introduced the fundamental building blocks of unit testing: test cases, assertions, setup and teardown routines, and test suites.

A decade later, in 1999, Beck and Erich Gamma released JUnit for Java. JUnit was the first widely adopted open-source unit testing framework. It brought test automation into the mainstream by integrating tightly with Java build tools and enabling rapid feedback for developers.

Version Control and Continuous Integration

As testing became more automated, another foundational shift was taking place: Version Control Systems (VCS) and Continuous Integration (CI).

CVS (Concurrent Versions System) was released in November of 1990, and it was one of the first centralized version control systems, allowing multiple developers to work on the same codebase while keeping track of changes in a shared repository. Before CVS, version control was typically local, meaning changes weren’t easily shared, tracked, or merged.

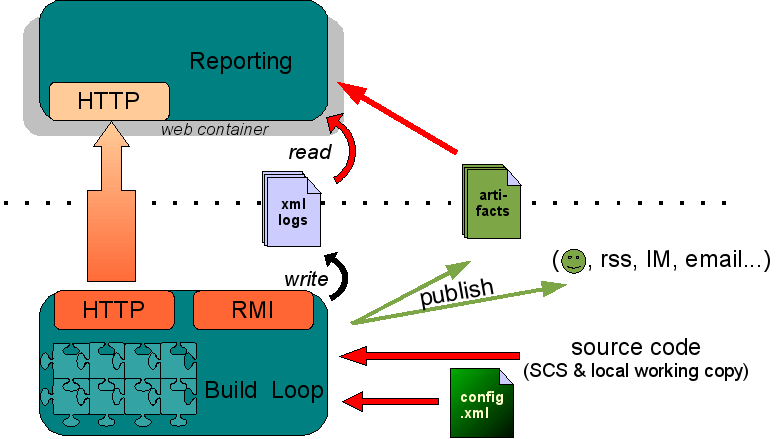

But version control alone wasn’t enough. So, in 2001 CruiseControl was released. Created by ThoughtWorks, this was the first open-source Continuous Integration system.

CruiseControl introduced the concept of a build loop, automated testing (via JUnit integration), and reporting dashboards.

Together, version control and CI laid the groundwork for the modern DevOps toolchain, where code changes are continuously integrated, tested, and shipped.

The Golden Age of Testing

The 2000s marked an explosion of innovation in automated testing. Selenium in 2004 allowed developers to write end-to-end and UI tests. It quickly became the go-to tool for front-end test automation.

On the CI front, 2005 brought Hudson, a more developer-friendly alternative to CruiseControl. Hudson offered a slicker interface, plugin architecture, and easier configuration, making it more accessible for teams of all sizes. It would eventually fork into Jenkins, which became the dominant CI tool for the next decade.

In 2005, we saw the origin of RSpec, easing developers into BDD. And by 2008, Cucumber brought BDD to the next level by introducing the Gherkin language — a plain-English syntax for describing software behavior.

JavaScript Testing Boom

By the 2010s, JavaScript had moved from being a browser-side scripting language to a dominant force across the entire web stack.

In 2011, Mocha was released as one of the first flexible JavaScript testing frameworks for Node.js. Mocha provided a simple yet powerful interface for writing asynchronous tests, and its modular design allowed developers to choose their preferred assertion libraries and reporters.

As the complexity of front-end applications grew, so did the demand for end-to-end testing. In 2014, Nightwatch.js appeared, building on top of Selenium to enable browser automation from within a Node.js environment. It offered an easy setup and syntax tailored to JavaScript developers, making UI testing more accessible.

That same year, Facebook open-sourced Jest. It bundled everything into a single tool, removing friction for developers and promoting best practices by default.

The push for better end-to-end testing continued in 2017 with the release of Cypress. Unlike Selenium-based tools, Cypress ran directly in the browser alongside the application, offering a more accurate and reliable testing experience. Then, in 2020 Playwright entered the scene. Created by former Selenium and Puppeteer contributors, Playwright introduced a modern approach to browser automation. It supported multiple browsers out of the box, allowed for headless and headful testing, and could simulate real-world user conditions like network throttling and geolocation.

AI Changes Everything

AI has changed how we develop software. If we look beyond the hype, LLMs are very capable of writing code and becoming collaborators in the testing process. They can take care of repetitive tasks and boilerplate.

With AI, developers can explore new workflows:

- Describe a feature in natural language, and get a suite of tests instantly

- Automatically update tests when code changes

- Use AI as a test reviewer to suggest missing coverage or redundant checks

We’re also seeing LLM-powered test runners integrated directly into tooling. A standout example is the Playwright MCP. MCP acts as a USB-like bridge between Playwright and an LLM, allowing developers to control browser automation through natural language instructions.

Conclusion

The story of automated testing is deeply linked to the evolution of software engineering. In the early days, testing was manual and costly. Waterfall development pushed it to the end of the process, treating it as a phase rather than a continuous practice.

Agile, version control, and CI lead to an explosion of testing tools across every layer of the stack. Testing became embedded in the development lifecycle. No longer an afterthought, it became essential to delivering reliable, maintainable software at speed.

As we move forward, the challenge will be to integrate new technologies like AI without losing the hard-won practices that make testing effective.

Thanks for reading and happy building!

Want to discuss this article? Join our Discord.